Here's what we had before the Affordable Care Act (ACA): private insurance, either from one's employer or purchased individually. For this to work, of course, just as any other business, insurance companies must make a profit, and that's harder when customers get sick; purchasers actually using their insurance isn't good for the bottom line. That's why there's so much talk about people with "pre-existing conditions". These are people who insurers know will cost them money and that's why people with "pre-existing conditions" were essentially uninsurable before the ACA, except as members of large employee pools comprised primarily of healthy people who had to buy in as a condition of their employment. And that's why insurance companies used to charge women, older people, smokers, and so on more; they were more likely to cost money. And that's why insurance companies also had policies such as lifetime caps on benefits. To stay in business, insurers have to make a profit. It's their reason for being. This system can work well for healthy people and insurance companies.

The second option is something like the ACA, where everyone, pre-existing condition or not, can buy insurance -- an appropriate thing to point out on Rare Disease Day 2017. As with auto insurance, the only way this is financially viable is if everyone is required to buy in; just as good drivers subsidize unsafe drivers, healthy people subsidize people more likely to use healthy insurance. Thus, the hated "mandate", the requirement that everyone buy in or be penalized on their taxes. Many detractors of the ACA believe the mandate can simply be eliminated, that a replacement for the ACA can cover as many people, as cheaply, without one. But, that's impossible. This is the same kind of privitized system that has worked without major snags for many years in Switzerland, for example. There, insurance is compulsory, and insurance companies must offer a basic plan which they aren't allowed to profit from although people can purchase bells and whistles, which is how the insurers make a profit.

The third option is the public option, often these days described as Medicare for all. Government-supplied health insurance, paid for by tax dollars. It's cheaper than the first two options in large part because it's non-profit, and the infrastructure required by private insurers to validate or deny claims doesn't exist. National health has worked well in many rich countries for decades, keeping costs down and providing access to medical care to all.

And that's it. There's no other "terrific" "cheaper" alternative anyone has thought of that can replace the ACA. The only options are a system that's totally private; something like the ACA with its mandate; and national health. Unfortunately, this wasn't very well explained when President Obama was working on the Affordable Care Act, and it's not being explained now. The Republicans in control of Congress aren't going to give us national health; and while it seems that many of them would be happy going back to what we used to have before the ACA, opinion polls are showing that people are less and less happy with that option. Will Trumpcare be Obamacare renamed, then? We'll have to wait and see.

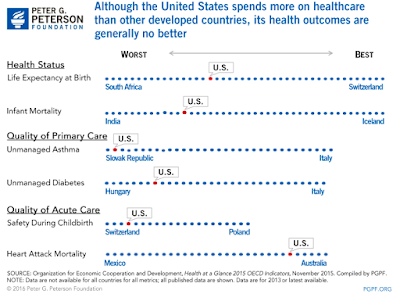

In any case, whatever system we adopt, we've still got problems. Although the rising cost of medical care in the United States has slowed some with the ACA, at almost 18% of GDP health care spending here is the most expensive in the world, far exceeding that of any other high-income country, most of which have national health care (e.g., source). In part it's because of the high cost of medical care, the higher use of expensive technology (e.g., MRI's, mammograms and C sections) and the exorbitant cost of pharmaceuticals. And this is even with limitations imposed by insurance companies to control costs. In addition, the cost of individual premiums has soared for people who aren't eligible for government subsidies to help cover the cost of insurance, in part, because fewer healthy people have purchased insurance than companies anticipated. And deductibles and co-pays have risen sharply. Insurance companies still have to turn a profit to stay in the health insurance marketplace.

|

| Source |

|

| Source |

So, even if Trumpcare is as terrific and as cheap as we've been promised, it's hard to see how it will cut the high cost of medical care, and make us a healthier nation. That is complicated, especially when private profit, rather than public health, is its fundamental basis.